The Asymmetric Capital Region Workforce Recovery

The Capital Region has more residents employed than ever before, but we’re about 12,000 non-farm jobs below our all-time high. Wait, what?

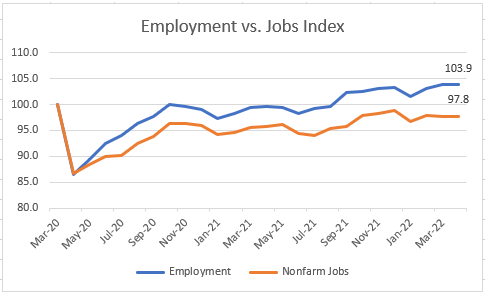

When the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released the April 2022 jobs data this week, the numbers showed a continuation of a somewhat confusing pattern – the number of employed residents in the Capital Region set another all-time high, almost found percent higher than when the pandemic started, while the number of jobs in the region stagnated about two percent below over the same time period.[1] Also, pre-pandemic, non-farm jobs were consistently higher than number of residents employed; as of May, there are 10,000 more people employed in Baton Rouge than there are jobs. How is that possible?

To get to the bottom of this puzzle it’s important to understand the difference between what these two metrics – employment and non-farm jobs – actually measure.

Employment or Jobs?

The easiest way to think about the difference between these two measures is that employment measures residents, while jobs measures businesses.

Employment tells us how many residents of our community have had employment in a given time period. This not only includes full-time, part-time, and contract work at businesses, but also anyone that did any work for pay or profit. It’s important to note that each resident is counted only once, even if they have multiple jobs.

Non-farm jobs, though, counts jobs at establishments rather than individuals. This measures how many jobs are at businesses registered in a metro area in at a given time. If one worker has multiple jobs, each job counts separately in this number. Another key note is that nonprofit and religious jobs are excluded from this measure.

What Caused the Divergence?

While there isn’t yet localized data to identify precisely what caused this divide, with a spike in employment and a drop in jobs, available data does shed light on patterns that offer suggestions. There are three likely causes.

1. Employment in Uncounted Fields: As explained in the previous section, there are a number of areas of employment that are not included in non-farm jobs beyond, obviously, farm jobs. Data suggests that during the pandemic, a number of people took steps to open their own business. Newer data confirms this trend, and suggests a strong increase in self-employment; non-farm jobs do not include a large chunk of the self-employed[2], while that group is included in the employment count. This could be as many as 1,700 jobs as of the third quarter of 2021, and even more now. In addition, non-farm jobs do not count employment in non-profit and religious organizations, so any job increase in those industries would not be counted. The shift in the way people work – for themselves rather than for a company – appears to be a big part of the employment vs. jobs shift.

2. Movement Away from Second Jobs: Another area in which data suggests jobs were lost but employment remained unaffected are second jobs. As explained earlier, if an individual has multiple jobs, that person counts one time for employment count, but each separate job they have is counted multiple times for non-farm jobs. If many people quit second jobs but keep their primary employment, this would skew employment vs. jobs in the way we’re seeing in the Capital Region – and the data available suggests that’s the case. In 2019, Baton Rouge had about 95,000 non-farm jobs classified as “extended proprietors,” which is defined as miscellaneous labor not considered to be a primary job. By 2021, that fell to 89,500, suggesting that there are 5,500 fewer of these non-primary jobs now than there were before the pandemic[3].

There’s one more data point that indirectly supports that movement away from secondary jobs that is negatively affecting the job count: the significant surge in demand for part-time workers. Part-time jobs are frequently secondary rather than primary employment, so movement away from secondary jobs would disproportionately impact the part-time job sector. Based on job posting analytics, in April 2019, there were 1,006 unique job postings in the Baton Rouge metro for part-time jobs; as of April 2022, there were 2,521 such postings.[4] This 151% increase from the same month pre-pandemic may indicate a large number of part-time employees didn’t return post-pandemic. This could be due to a number of factors, such as stronger household balance sheets, better primary job opportunities due to the tight labor market, the decision for one family member to spend more time at home in a dual-worker household, or a number of other reasons.

3. Remote Work: The third major factor could be a pattern seen nationally occurring in the Baton Rouge metro as well – the rise of remote work. In 2019, over 3,100 residents of Baton Rouge had work addresses outside of Louisiana.[5] These included places like Houston, Dallas, Memphis, Atlanta, and other large metros. Unfortunately, this data lags two years, so on a localized level we’ll be unable to tell exactly how much this factors in to the employment vs. non-farm job discrepancy we are currently seeing. However, mid-sized metros across the country are taking advantage of this trend, as their residents work remotely for companies in major metro areas and then spend their incomes locally in their mid-sized metro homes.

While this topic is interesting to opine on, there are real-world takeaways for businesses and community leaders. Pre-pandemic, the Capital Region had about 1.3 job openings for every unemployed resident looking for a job; the ratio is now up to 2.4, translating to about 13,000 people available to fill more than 31,000 open jobs.[6] The labor market is as tight as it has ever been.

Taking all this data together, the “what does it all mean?” comes out to something like this: the all-time high employment numbers likely indicate the below-pre pandemic job numbers are not as big an issue as they appear to be, as many people are now working in roles that go uncounted in terms of non-farm jobs. In addition, it appears that many residents dropped secondary or part-time roles, something that would be possible with higher wages at primary jobs and strong household balance sheets. However, demand for talent is real, and filling even half the current open jobs would rocket the region to an all-time high in jobs. The longer-term solution to solving this tight labor market is to do a better job retaining the 55,000+ students currently in higher education in the Capital Region – on this front, BRAC and higher education institutions have collaborated on Handshake, a platform to connect students to local internships, which allows free access and job postings for businesses of all sizes. In the meantime, employers have the opportunity to fill part-time or entry roles by digging into potential worker pockets that are too-often ignored when the labor market isn’t as tight: high schoolers looking for work experience, student workers, or those looking to reintegrate as they enter the community from incarceration, to give a few examples.

[1] Employment and non-farm jobs are both available through BLS; BRAC analysis

[2] According to BLS, the only self-employed that are included in non-farm jobs are those that have registered their businesses, which would not include a large group of 1099-type employees.

[3] Emsi Occupational Data, Q2 2022

[4] Emsi Job Posting Analytics, May 2022

[5] US Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies, BRAC analysis

[6] Emsi Job Posting Analytics, May 2022; BLS