What’s in a County?

We zoom in this week to look at counties and parishes that are supplying talent to the Baton Rouge Area, as well as taking talent from the Capital Region

[Part 2 in a BR by the Numbers series on Capital Region migration patterns]

Last week we discussed an important migration-related trend in the Capital Region: about two of every three young professionals moving to Baton Rouge come from elsewhere in Louisiana. As our region continues to grapple with an unprecedented number of job openings, understanding our region’s strengths and limitations regarding migration patterns can help business and civic leaders develop appropriate next steps for attracting talent to fill these open jobs.

This week, continuing our series on Capital Region migration patterns, BR by the Numbers looks at Internal Revenue Service (IRS) migration data that covers filing years from 2015 through 2020, and therefore tracks migrations from 2014 through 2019. The IRS uses changes in tax filers’ addresses to determine migration status1; the agency then organizes these data to show state-to-state migrations and county-to-county migrations. Key findings are discussed here.

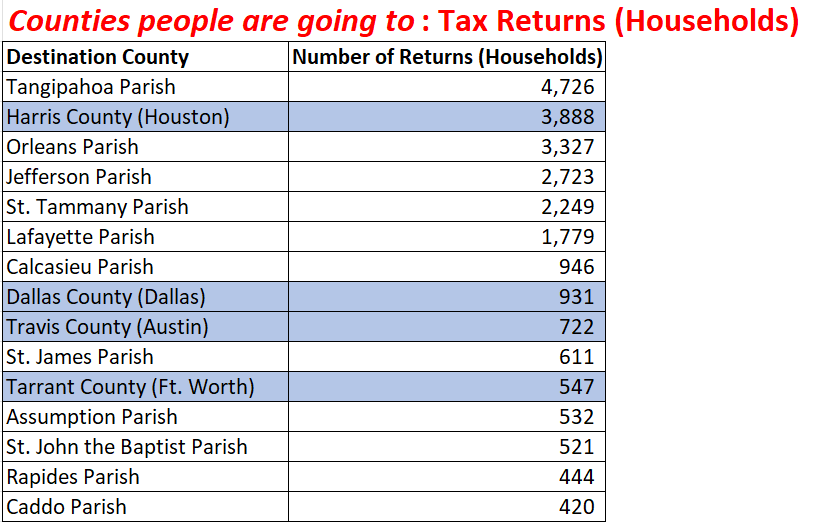

Almost 2,900 households moved to Baton Rouge from Houston and Austin

From 2014 through 2019, Harris County (Houston) and Travis County (Austin) were the 4th and 13th most common origin counties for households moving to the Capital Region, respectively2. The table below shows the total number of households leaving each county and migrating to the Capital Region. Harris and Travis were the only two out-of-state counties included in the top fifteen origin counties for movers to Baton Rouge. Other parishes from which households moved to the Capital Region in high numbers include Tangipahoa (4,595 households), Jefferson (3,073), and Orleans (2,429).

Harris County’s inclusion is unsurprising. Houston is the closest major metro to Baton Rouge, and Harris, which has the third-largest population of all counties nationwide, is a likely migration partner because of both geographic proximity and sheer size. Travis County’s inclusion, however, is a bit more surprising.

Dallas County, the central urban county in Dallas, has a population more than double that of Travis County and is slightly closer to Baton Rouge. Despite that, just 400 households moved from Dallas County to Baton Rouge which is about 40% less than the number of households that moved from Travis County. Only 198 households moved from Shelby County which has a smaller population than Travis but is about an hour and a half closer to Baton Rouge. Travis County’s inclusion among the top origin counties for movers to Baton Rouge suggests stronger ties between Baton Rouge and Austin that go beyond geography and population.

More than 4,600 households moved from Baton Rouge to urban counties in Houston or Austin, and another 1,400+ moved to Dallas/Fort Worth

Baton Rouge households moved in droves to some of the most populous counties in Texas including Harris, Dallas, Travis, and Tarrant. After Tangipahoa Parish, Harris County was the second most popular destination for households leaving the Capital Region.

The New Orleans metro is also well-represented with about 8,300 households moving from Baton Rouge to Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Tammany combined.

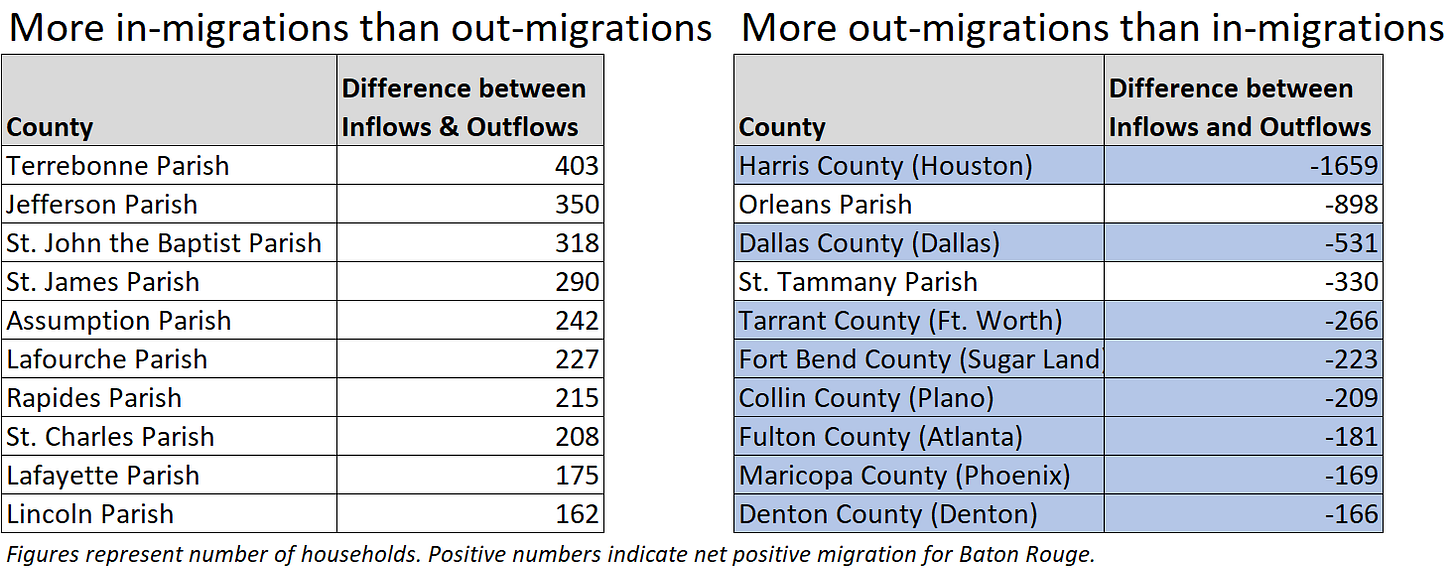

The Capital Region’s migration advantages are with other Louisiana parishes, while a mix of in-state and out-of-state counties show net-negative migration

Baton Rouge had net-positive migration with several Louisiana parishes but experienced net-negative migration with several in-state and out-of-state counties. From 2014 to 2019, 684 households moved from Terrebonne Parish to the Capital Region while 281 moved from the Capital Region to Terrebonne, resulting in the net-positive migration of 403 households visible in the table below.

Eight out-of-state counties rank among the top ten for most significant net-negative migration with Baton Rouge. Two Houston metro counties (Harris and Fort Bend) are featured, as are four Dallas-Ft. Worth metro counties (Dallas, Tarrant, Collin, and Denton). Urban counties in non-Texas metros are included as well: 334 households moved from Baton Rouge to Fulton County (Atlanta) compared to just 153 that moved from Fulton to Baton Rouge. A similar trend emerged with Maricopa County (Phoenix).

The findings here are important to consider in tandem with last week’s insight that two of every three young professional movers to Baton Rouge come from elsewhere in Louisiana. Our metro is attracting households from across the state, but we’re losing households to major metros beyond state lines. We’re doing better at attracting households from some metros (Austin) compared to others (Dallas). Further analysis of this sort of trend is warranted.

As we often point out, this trend of losing talent to out-of-state metros is not unique to Baton Rouge. This data provides strong evidence for the importance of key goals included in BRAC’s five-year strategic plan, like increasing the number of local college graduates hired by Baton Rouge Area employers. BRAC is already taking steps to make this a reality through hiring initiatives like Handshake (careers targeted for local graduates) and BR Works (careers and upskilling opportunities targeted for area residents). While BRAC continues to take steps towards retaining local college graduates and residents in general, it’s important that business and civic leaders across the metro strive to do their part in retaining area talent.

Technically speaking, the IRS assigns a geographic code to the address of each tax filer. If a filer's address changes but their geographic code does not change, then that tax filer is classified as a non-migrant, even though they moved to a different residence. This may be the case if a tax filer moves into a different residence located on the street of their current residence.

IRS guidance indicates tax returns can be used to estimate number of households with the idea that one household files on

e tax return. See: U.S. Population Migration Data: Strengths and Limitations