Why Not Us? Profiling Greenville's Progress Ahead of BRAC's Canvas Trip

Greenville has earned a reputation as a great place to live, work, and play. What will Baton Rouge's leaders learn from this superstar mid-sized metro?

Next week, more than a hundred of Baton Rouge’s business, community, and political leaders will travel to Greenville, South Carolina for BRAC’s Regional Canvas Benchmarking Workshop. Greenville, the 61st largest metro in the country (we’re 67th), has earned a reputation as a great place to live and visit; it was named one of the best cities in the US for workers to relocate to during COVID and, this year, it garnered a spot on CNN Travel’s best places to go for fall list. Downtown revitalization, increasing residential density, and an industry overhaul have helped turn Greenville into a superstar mid-sized metro, but these are also factors we highlight as ongoing strengths in Baton Rouge. Similar populations, similar trends, similar geographies – taken together, these factors beg the question: Why not us?

This week’s substack addresses this question by looking at Greenville’s reputational rise through the city’s downtown and economic transformations.

Downtown Revitalization and the Power of P3s

In 1968, Greenville commissioned its first downtown development plan, a full 30 years before Baton Rouge’s first major downtown master plan, Plan Baton Rouge, which outlined strategies for our own downtown’s revitalization. Greenville’s plan was progressive for its time - it recommended “making Main Street a pedestrian friendly environment,” a strategy Baton Rouge has employed recently through initiatives like the Government Street Road Diet.

But strategic development plans for urban areas are nothing more than that - plans. It takes the collaborative efforts of stakeholders including business leaders and elected politicians to bring development plans to life.

Greenville has been a leader in P3s, or public-private partnerships, over the last four decades. Between 1982 and 2016, $126 million in public funding was leveraged to get $487 million in private funding for 19 major downtown projects in Greenville1. Momentum for these projects picked up in the 2010s, with 36% of the public funding and 51% of the private investment coming between 2010 and 2016.

These 19 headline-making projects leveraged P3s to “direct development according to its Master Plan.2” The collaboration between the public and private sectors over the last half-century turned paper plans into reality, and these efforts started in 1982 with what the Greenville Journal called the “grandaddy of P3s.”

Greenville Commons, a luxury hotel and convention space and the city’s first P3, was built as a partnership between the City of Greenville and the Hyatt Regency Corporation. Greenville Commons, located along Greenville’s Main Street, was one of the initial anchor projects in the downtown revitalization effort. The $10 million in public funding for this project included $7.5 million from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and the US Department of Commerce. Hyatt put up nearly 10 times the amount of local public funding for the initial project, and that initial investment led to additional investment 30 years later when, in 2011, JHM Hotels announced it was renovating the same downtown property. The renovation of this building, now NOMA Tower, also included the renovation of the surrounding public space, now dubbed NOMA Square, which hosts public events for the city. The renovation was completed in 2013 to the tune of $11.3 million in total investment with 92% of that funding coming from private dollars.

Project ONE, Greenville’s most-expensive P3 through 2016, transformed the center of Greenville’s downtown into a vibrant mixed-use corridor. Completed in 2016, the project used $11.5 million in public funding to leverage $118 million in private financing to create an active pedestrian-oriented corridor that features corporate headquarters, retail and restaurant spaces, and the current home of Clemson University’s MBA program. As part of the project, $4 million of funding put up by the City of Greenville was used to redesign the surrounding public plaza and the major intersection at the foot of the development. Today, that four-way intersection features wide, shaded pedestrian walkways going in all directions, public seating, and public art installations.

Two big things stand out about these 19 projects. First, these projects are fundamental to Greenville’s long-term orientation, one in which both private developers and the public sector accept these projects as catalysts for Downtown Greenville’s long-term growth. Much of the public funding for these projects has come through tax increment financing districts which essentially bank on future property value increases to fund current capital improvements. This financing mechanism reflects both the long-term orientation and the confidence/cooperation present between the public and private sectors.

The second is the prevalence of mixed-use planning in these projects – most feature a combination of residential, commercial, and/or office space. Several of these projects include improvements to surrounding parks and public spaces, a type of strategic placemaking that encourages further economic development. Public funding for several of these projects has gone to the construction of parking garages to help meet parking minimums included in the local land development regulations. And, from 2007 through 2016, nearly all the major projects with significant public-funding included a residential component. Increasing residential density in Downtown Greenville has helped the city achieve the vibrancy it planned for over fifty years ago in its original downtown revitalization plan.

Work, Play, and Live Downtown

Earlier this year, BR By The Numbers highlighted Downtown Baton Rouge’s impressive 25% population growth from 2010 through 20203. During that decade, Greenville added 1,000 more residents to its downtown than Baton Rouge, registering a 40% growth rate.

Large-scale projects beginning in the 1980s through the early 2000s brought to Downtown Greenville cultural amenities like Greenville Commons, Peace Center, and Fluor Field, and these projects helped spark residential demand around these spaces. Young professionals in addition to retirees and students are groups that are typically more interested living in downtown areas, and Greenville has done a good job at attracting these groups and others to live downtown. From 2002 through 2019, the number of people with a job living in downtown Baton Rouge declined while, in Greenville, it nearly doubled.

In 2010, 28% of people living in Downtown Greenville had a job compared to 48% in Downtown Baton Rouge. Just a decade later, 37% of Downtown Greenville residents had a job compared to 40% in Downtown Baton Rouge. Based on these estimates, people with a job accounted for 5% of Downtown Baton Rouge’s population growth between 2010 and 2020 compared to 60% of Downtown Greenville’s.

People without a job who live downtown includes kids in families, students enrolled in higher education, and retirees. Both groups – people with and without jobs – contribute to vibrant downtown areas. Disposable incomes, however, tend to be greater for people with a job, and these disposable incomes are important for supporting downtown shops and restaurants. Also of note is that a number of these workers living in Downtown Greenville live in income-restricted apartment units, a feature of several of the residential projects built in Downtown Greenville over the past few decades.

Industry Transformation

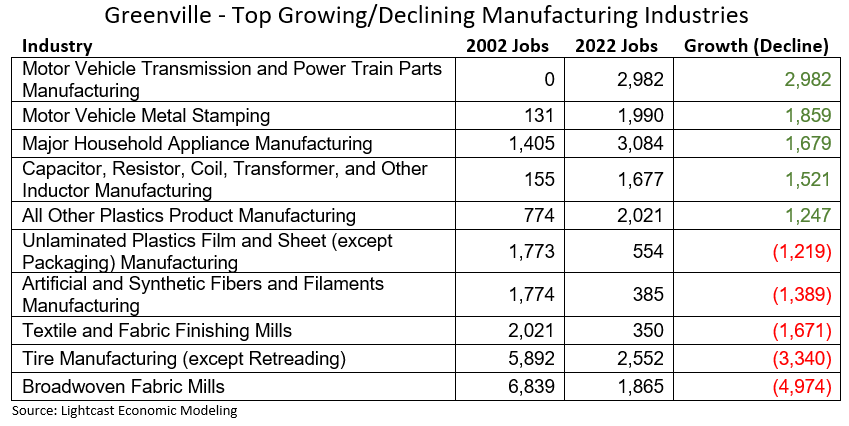

Another oft-cited factor in Greenville’s rise is its transformation from a textile manufacturing-focused economy to one that’s more diversified while still leaning on its manufacturing roots. Looking at the top growing/declining manufacturing industries in Greenville, automotive manufacturing jobs have grown by the thousands over the past 20 years while textile-related manufacturing jobs have declined significantly. Greenville took its legacy industry and adapted its assets to the modern economy, not dissimilar from Baton Rouge’s own efforts today.

Baton Rouge is undergoing its own economic transformation, leaning on its global expertise in the petrochemical and other heavy industrial sectors to accelerate growth in emerging sectors like transitional energy. High-paying industries employing engineers and skilled trade workers are growing to meet demand in emerging sectors.

Baton Rouge’s ongoing economic transformation parallels Greenville’s, and industry leaders here are already taking a page out of Greenville’s book. Although not a public-private partnership for a specific project, BRAC’s recently-announced Carbon Reduction Alliance is a great example of the power behind collaboration between government and business. By bringing together industry partners, public sector organizations, and higher education institutions, the Baton Rouge Carbon Reduction Alliance will lead to greater cross-sector collaboration and, in the long-term, mutually beneficial outcomes based on a shared vision of success. Sounds a lot like Downtown Greenville.

Wrapping up – Why not us?

Baton Rouge and Greenville are not all that different (in fact, according to the Greenville Chamber, Baton Rouge is tied with Columbia as the third most-similar metro in the country to Greenville). Compared to Greenville, Baton Rouge has some competitive advantages – our metro is home to the state’s flagship university, and Baton Rouge Metro’s GDP was $9 billion greater than Greenville’s in 2020 despite having 6% fewer residents. Gone unmentioned in this piece were Greenville’s successful efforts to transform its downtown Reedy River into a vibrant public space – the Reedy River is nice, but its grandeur doesn’t compare to the mighty Mississippi.

This brings us back to the question posed at the outset: why not us? Why has Greenville earned the reputation of a superstar mid-sized metro and not Baton Rouge? One of the major differences is Greenville’s intense focus on enhancing its downtown amenities and, more importantly, the level of collaboration that’s taken place over the last 50 years between public agencies and private developers to turn those amenities from plans into reality. As community and business leaders travel to Greenville to learn best practices regarding talent, quality of life, inclusive development, and other topics, it’s important to note that based on the data, there’s no reason the Capital Region can’t have many of the assets they see.

https://citygis.greenvillesc.gov/downtownreborn/index.html

https://greenvillejournal.com/syndicated/how-public-private-partnerships-bring-development-to-fruition/

The boundaries of the Downtown Development District are used to define Downtown Baton Rouge.

Sources:

https://www.greenvillesc.gov/ImageRepository/Document?documentId=11533

https://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/4/prweb10670909.htm

https://citygis.greenvillesc.gov/downtownreborn/index.html